Building the playspace

Creating a foundation that supports iteration.

Introduction

In the last entry I outlined the initial concept for the game - an extremely reductive version of what I think the game could be.

This phase of development was about preparing the playspace and pieces for gameplay. Rather than focusing on hand-crafted content, the priority was building tools and systems that would support fast iteration later. The goal was not to create a “final” map, but a flexible foundation I can easily tune, break and rebuild as the design evolves.

Procedural Generation as an Iteration tool

I chose to introduce procedural generation early, despite the upfront cost, because it dramatically reduces iteration cost later. The project requires large maps that can embody a journey and building these by hand and editing them later would take a long time.

The Current Method:

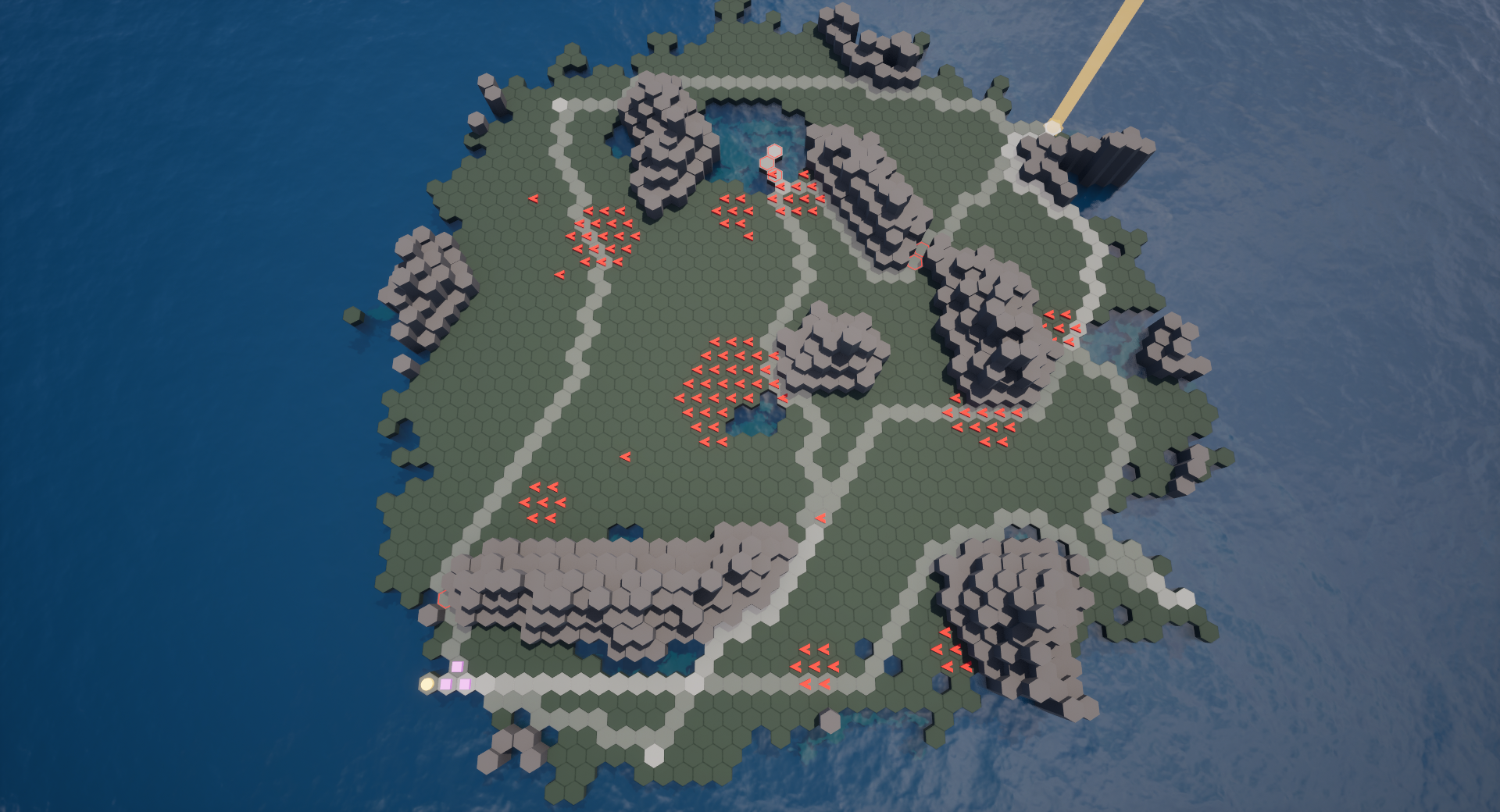

- Generate a landmass shape of a specific size using drunkards walk.

- Iterate over that landmass using “Terrain layers” (e.g. grass, water, stone)

- Each terrain layer uses its own noise map to decide which tiles should become that terrain.

With this system in place, I now have an easily tuneable foundation for the playspace. I can quickly update the size of the map for testing and modifying how terrain is generated is just a case of modifying variables. Adding a new terrain layer is as easy as adding a new set of data to an array.

Another benefit of using procedural generation here is that it will keep playtests fresh as a variety of scenarios can emerge from it.

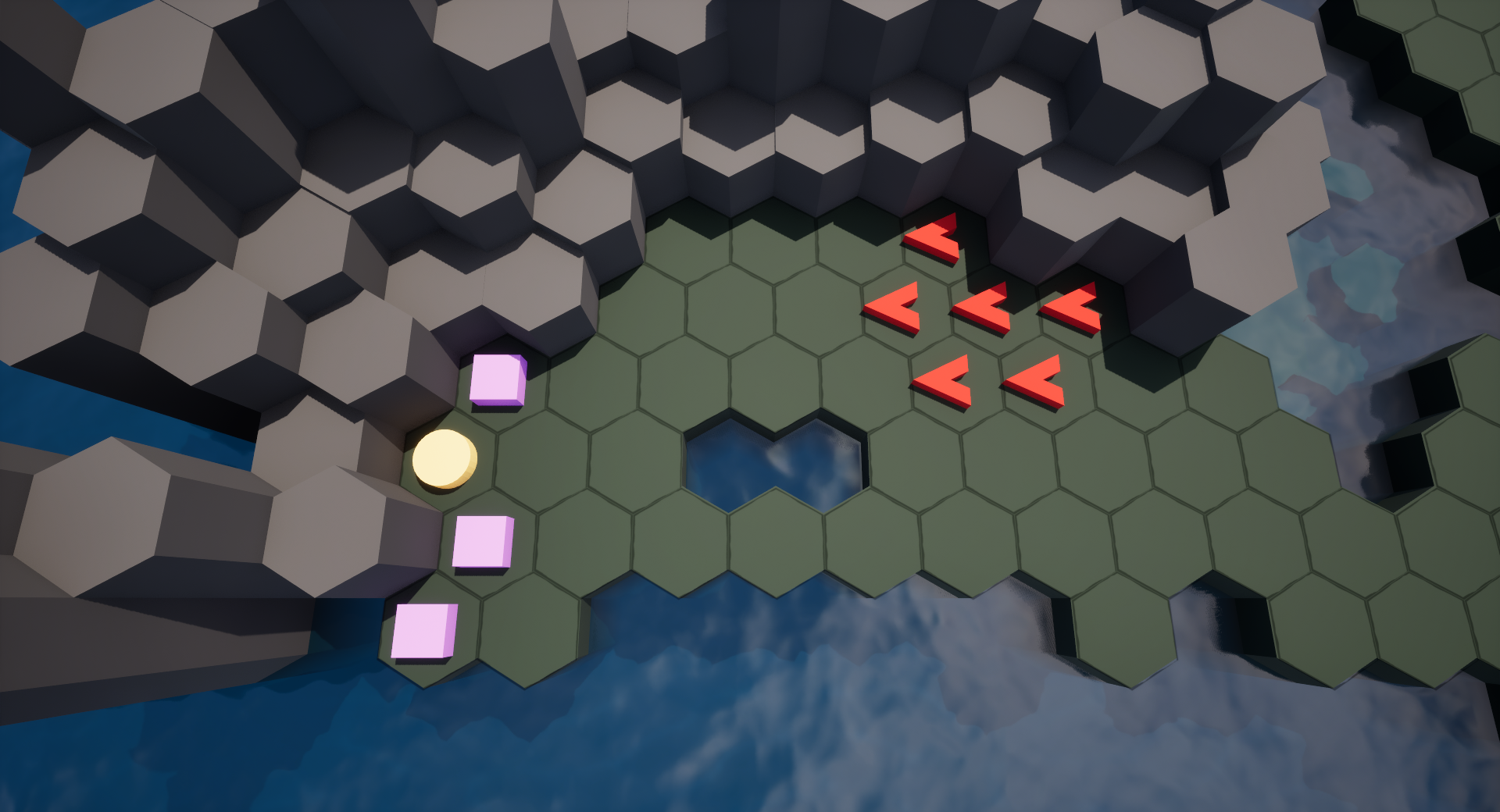

Readability-First Character Representation

All characters are represented using simple shapes, as early prototypes should be. While these are of course placeholders, they can still intuitively communicate their role.

- Vassals are cubes, communicating stability and solidity.

- The Burden is a disk, which feels friendly but weak and vulnerable.

- Enemies are triangles, with a notch cut out to show facing direction.

Enemy directionality is important because enemies need to be predicted and planned around. Player-facing direction currently doesn’t convey useful information, as aiming and movement are independent, so it’s intentionally omitted.

To support readability, I darkened the environment and avoided using shapes similar to hexes for characters. This keeps characters visually distinct from the grid, improving clarity.

Temporary Spawning Rules

To guarantee space for gameplay, the player currently spawns in the bottom-left of the map and the goal is placed in the top-right. Regardless of landmass shape, this diagonal placement ensures a long distance between the player and the goal, creating room for meaningful decisions along the way. This is a temporary rule, but it provides a reliable structure while other systems are developed.

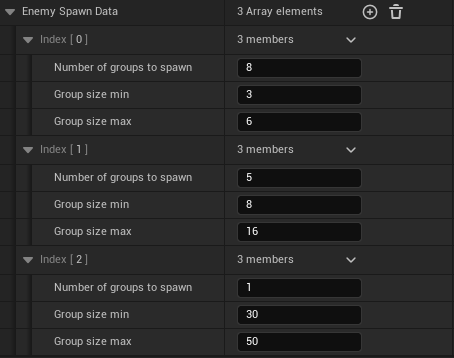

Enemies spawn in randomly distributed groups. These groups are defined using simple data, as shown below:

This approach avoids baking enemy placement into the map and allows spawning rules to evolve independently. Later, enemy placement will likely respond to predicted player paths, for example concentrating larger groups along the shortest route to the goal to push players into detours. The current system exists to be replaced, not because it’s the final solution.

Ensuring The Map is Navigable

Procedural generation always carries the risk of creating unwinnable maps. To guard against this, I built an A* pathfinding component that operates on a terrain movement cost map.

Each character can define how expensive different terrain types are. For example, grass might have a cost of 1, while water and stone have extremely high costs. As long as a terrain’s cost exceeds the maximum movement points a character could ever have, that terrain is effectively impassable.

This component is reusable and will support anything that needs to reason about movement across the hex grid.

Currently, it’s used by a system called Path Forgers. These entities pathfind from the player spawn to a random point on the map, then continue on to the goal. Unlike characters, they are not limited by movement points. Their purpose is to ensure there are always multiple viable routes through the map.

Path Forgers treat non-navigable terrain as expensive rather than impossible. By tuning these costs, I can control how often they choose to carve through stone or water instead of taking a longer route through grass. If no path exists at all, they will always carve one.

The random midpoint is a simple, temporary solution, but an important one. It prevents Path Forgers from creating a single optimal corridor straight to the goal. Instead, they encourage branching routes and meaningful navigation choices. This impact will be improved later as I add more intelligent "stops" on their routes.

In the image above, tiles the path forgers have touched are highlighted in white. Tiles they have changed contain a red hexagon.

What’s Next?

With these systems in place, I now have a stable playspace that supports experimentation rather than fighting it. I can change scale, density and structure without rework, and I can layer gameplay systems on top without worrying that the map itself will collapse under iteration.

The next phase is creating gameplay by adding in basic enemy and player behaviours.