Turning an Idea into Rules

Using design drivers to focus creative exploration.

Introduction

In the previous entry, I focused on unpacking the High Concept Document for Project: Fellowship — clarifying the vision, themes and player experience I want the game to support and explaining where my focus would be during the earliest stages of development. That work was about setting direction, not solving design problems yet.

This entry tackles the next step: turning that direction into something concrete. The goal here is not to present a complete or balanced design, nor to fulfil every ambition laid out in the High Concept Document. Instead, this is about reducing the idea down to the smallest coherent set of rules from which a first prototype can be built and iterated on.

At this stage, the focus is on defining starting conditions. Many systems are intentionally incomplete or crude. That’s by design. Refinement comes later, once there’s something concrete to test.

Design Drivers

One of the main challenges at this stage was managing creative exploration without letting the project sprawl. Early design generates ideas faster than they can be evaluated and without structure it’s easy to drift into feature creep or premature implementation.

To keep momentum without overscoping, I framed the notes that emerged from analysing the HCD and its referenced games and genres as design drivers rather than features. These drivers helped turn a storm of ideas into a directed process, allowing exploration while keeping the focus on the prototype.

Most notes naturally fell into three categories:

Goals

What the design should aim to achieve. Goals describe the experience I want the systems to support and provide criteria to evaluate decisions against.

Constraints

Deliberate limits introduced to protect those goals. Constraints reduce the solution space not to simplify the game but to keep it readable and coherent.

Questions

Unresolved concerns framed as problems to test later. Questions allow ideas to be explored without committing to them prematurely.

For example, I developed the goal “Combat should be deterministically resolved” in support of deckbuilding synergy. Many tactical turn-based games rely on hit chance systems, but I believe this would conflict with the set-up and pay-off gameplay central to deckbuilders. A missed attack could undermine a carefully planned sequence, invoking frustration. From this came the constraint “No hit chance system”.

That goal itself represents an assumption, one I want to test by asking the question: Does combat present patterns that are complex enough to make deterministic resolution engaging while remaining readable at a board-wide scale?

Potential answers can be explored later if needed, such as introducing randomness elsewhere in the system, limiting player information or experimenting with chance-based bonuses (like critical hits). At this stage, they remain possibilities rather than features. Exploring these questions may lead to changes in the goals, which in turn can shift the constraints.

Framing ideas this way allowed creativity to flow while keeping the first playable core focused. Goals set direction, constraints establish boundaries and questions preserve flexibility, creating a structure that supports experimentation without bloating the prototype.

The Concept

With the design drivers in place, the next step was reducing the original vision to a minimal, playable core. Many ideas from the HCD were deliberately left out — not rejected, but unnecessary for this first prototype.

This reduced concept represents my first hypothesis for how the core gameplay of Project: Fellowship could function effectively. It was selected from multiple candidate concepts based on how well it aligned with the design drivers outlined earlier in the process. I’ll explore the reasoning behind these choices in the sections that follow, highlighting how they shaped the foundation for the first playable prototype.

.png)

At its core, Project: Fellowship is about positioning and visibility. The hex grid and terrain types establish a simple spatial language that all other systems build on.

At this stage, the playspace is intentionally minimal. Terrain defines only two things: whether a tile can be entered and whether it blocks line of sight. There are no elevation rules, cover modifiers or terrain-based effects yet.

This provides just enough structure to test movement, enemy detection and combat mechanics without adding unnecessary noise. Anything more would introduce complexity before I know where it’s actually needed.

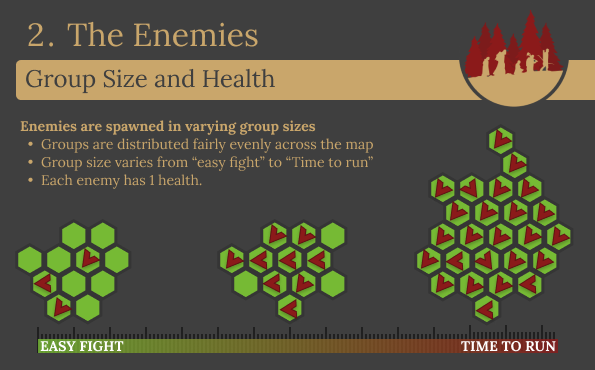

One idea is clearly outlined in the HCD: combat should involve large groups of enemies. The fantasy is not a handful of elite opponents, but overwhelming numbers that pressure positioning and movement.

This immediately raised a concern:

How do you represent information like health, damage and state clearly when there may be dozens of enemies on screen at once?

Traditional per-enemy UI quickly becomes noisy and hard to read at that scale: below is typical view of the late game in Civilisation VI, demonstrating how too many UI elements on the board impacts clarity.

To support the goal of game state readability at a map-wide level, I introduced the constraint of “No Enemy UI”. This influenced many downstream decisions, the first being that enemies only have 1 health. This aligns with the concept of large groups and spatially focused gameplay, essentially mapping enemy health to the board — the group itself becomes the health bar.

There are many ways enemy health could eventually be represented more explicitly or diegetically. For this first build, however, the goal is to remove unnecessary complexity and validate whether individual enemy health is even required.

.png)

Enemy AI is intentionally minimal at this stage. I could have reduced it further by making wandering enemies stationary, but I chose not to based on my experience with stealth games: stationary enemies produce very simple, quickly solved patterns. Without movement, uncertainty disappears too quickly and basic stealth gameplay becomes trivial.

Right now all I need is for enemies to support stealth and combat conflicts. When one enemy in a group spots a player character, the entire group enters the attack state, reinforcing the idea of treating groups as single entities.

.png)

.png)

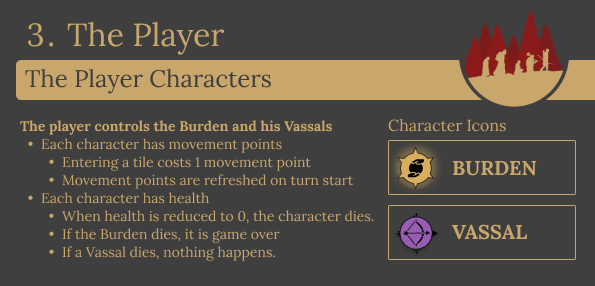

The Burden and the Vassals

The Burden is the only essential character, framing the game as an escort-style journey. This immediately raised a concern for me: escort mechanics often feel frustrating, with the escorted character acting as a liability rather than a meaningful part of the experience.

This led to an early design goal: the Burden should feel both vulnerable and powerful.

He cannot attack directly and must be protected, but he is also the source of the player’s most powerful utilities. His power is channelled through others, meaning he is only strong when surrounded by allies and in turn they become stronger.

My theory is that this structure satisfies that goal, reinforces the central themes of the vision and supports clarity and depth without overwhelming the player or requiring complicated UX journeys.

Mapping Damage to the Board

This damage system was inspired by the idea of mapping enemy health to the board. As explored earlier, the size and shape of an enemy group is its health.

The goal here is to reframe combat as a positional and mathematical problem:

How do I line up enemies, terrain and attacks to remove as much threat as possible each turn?

The player is not guessing or relying on random inputs. Each turn presents a new spatial pattern to resolve. Uncertainty can be reduced through observation, planning and action.

This mechanic is intended to act as the foundation of combat decision making, the seed from which the rest of the combat design grows. Before expanding on it, it needs to be tested in a clean environment. I want to understand how players respond to solving this type of problem every turn and adjust or reject the idea based on that feedback.

Reducing Complexity: Boons and Vassal Attacks

Project: Fellowship sits at the intersection of several complex genres: tactical turn-based combat, deckbuilding roguelikes and large-scale strategy. Simply combining their mechanics would create overwhelming complexity. Depth is the goal — not complexity for its own sake.

One key decision here was where complexity should live. For example, I deliberately chose to omit an accuracy system. Tactical turn-based shooters often rely on hit chance to add variability, but in a synergy-focused deckbuilder context, randomness would undermine planned sequences of Boons and Vassal actions. A missed attack could break a carefully arranged combo, preventing the pay-off the player may have been working up to. Keeping outcomes deterministic preserves the set-up and payoff flow and supports strategic depth.

Another way I tackled complexity was by defining how actions and cards interact. If every character had their own hand of cards and each card defined its own targeting rules, ranges and effects, the onboarding cost would be enormous. The player would be forced to evaluate not just what a card does to its target, but all the spatial permutations of how it could be used.

To avoid this, I separated responsibilities:

- Vassals have fixed, reusable actions with consistent ranges and rules

- The Burden holds all cards (Boons), which modify those actions rather than replace them

This structure has several advantages. Cards are simpler and faster to learn. Action ranges become familiar over time. The UX is cleaner, with cards applied to characters rather than targeted through complex spatial rules. Most importantly, the Burden’s role as a force multiplier is reinforced mechanically.

For now, there is just one type of Vassal with one type of attack and Boons just add damage, but it opens doors to a large design space.

A Finite Deck and Scarcity

Influences from survival and journey-based games suggested experimenting with scarcity, breaking free from traditional resource loops used in similar games and shifting focus toward longer-term resource management.

For this first concept, the Burden’s deck is finite. There is no automatic card draw each turn and no way to replenish the deck yet.

This is almost certainly not the final solution. It is, however, the simplest way to explore longer-term resource management and pacing without introducing additional systems.

By controlling the distance to the objective and the size of the deck, a single playthrough can be roughly paced around the use of that limited resource. Future iterations can explore recovery, expansion or alternative reward loops once this baseline is understood.

Card Draw on Enemy Kills

Rather than drawing cards at the start of each turn, new Boons are drawn when the player defeats a yet-to-be-defined number of enemies. The goal here is: “effective combat increases the player’s power potential” – Future tuning of this variable will aim to serve that goal.

This ties combat more directly into the broader journey and acts as an early form of reward structure. It incentivises engagement with enemy groups rather than pure avoidance, without forcing it.

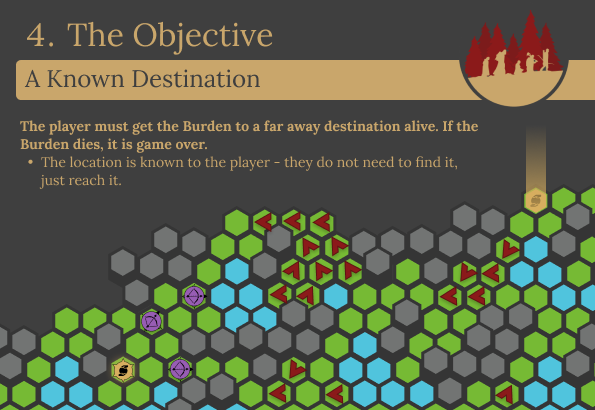

The objective is simple: escort the Burden to a known destination.

By removing the need to discover the objective, the focus stays on navigating obstacles rather than covering ground. The player always has clear direction, providing a constant anchor for decision-making. This means enemies become obstacles, not boundaries. The player must overcome them to get where they want to go, rather than decide where they want to go based on where the enemies are.

Conclusion

This entry documents the point where Project: Fellowship shifts from vision to action. By using design drivers to shape and reduce a wide range of ideas into a minimal set of interacting systems, I now have a foundation that is concrete enough to test, but flexible enough to change.

Nothing here is presented as final. Many decisions are deliberately reductive, and some assumptions will almost certainly prove wrong. That is the point. This concept exists to expose problems early, validate or challenge my design instincts and reveal where uncertainty is actually needed.

In upcoming entries, I’ll move out of theory and into implementation, building the first playable prototype from this foundation and beginning the process of answering the questions raised here through playtesting.