Developing the High Concept

Providing creative direction without building a cage.

Introduction: A Design Compass

When you first have an idea for a game, it’s easy to let your imagination run wild - sketching out systems, interactions, and mechanics long before you ever touch a prototype. Then, once playtesting begins, you realise some of those ideas don’t quite work. Others might need to change completely. That’s normal - it’s called iteration, and it’s at the heart of game development.

The challenge is that after countless iterations, you can lose sight of the bigger picture. You start focusing on small problems instead of the player’s overall experience. The original vision - the why behind the project - begins to blur. That’s where this document comes in.

Its purpose is to capture the experiential goals of the game: the fantasy it aims to deliver, the feelings it hopes to evoke. It isn’t here to dictate rules or lock down mechanics - those will evolve. Instead, it exists to align everyone’s understanding of the vision and serve as a beacon throughout development.

This document doesn’t oppose iteration; it gives it purpose. Systems will change, mechanics will break, and ideas will be reborn — but the vision should remain. It’s both a compass and a benchmark: guiding development while giving you a vision to check your evolving gameplay against.

Of course, this document isn’t safe from iteration either. The prototype exists to test whether the concept delivers on its vision - to validate the experience it describes. If the prototype achieves what’s written here but players don’t respond as hoped, then the vision itself must be re-examined. Even a compass needs recalibration from time to time.

Ultimately, the High Concept doesn’t lock the game in place — it simply ensures that every iteration serves the same experience. It provides creative direction without dictating the form that direction takes.

A note on visual references:

I’ve chosen not to include visual references at this stage. My focus is on shaping the experience through systems first - to understand how the game plays and feels before defining how it looks.

Visuals are, of course, an important part of the player experience, and I intend to explore them as part of the prototype. My goal is for the art to serve the gameplay, not dictate it. I anticipate that visual constraints will emerge naturally through development - particularly from procedural generation and the tile-based world.

I don’t expect those to be the only sources of constraint, but they’re where my focus lies for now. Once those foundations are understood, the art direction can grow from them organically.

The High Concept: An Overview

The first page is designed to get the reader imagining the game immediately. In just a few paragraphs, it paints a picture of what the player is doing, what the world feels like, and what emotional arc they might experience.

This page is where the creative vision lives - the spark that sets the whole project in motion.

.png)

The Player Experience Goals (Gameplay Pillars)

The pillars aren’t about features or systems - they’re about experience goals. They define what the player should feel, rather than the specific actions they can take.

They serve both as sparks to inspire design and as lenses through which to evaluate decisions. For example, if I’m designing consumable items the player can find and use along their journey, I might initially imagine something that helps them evade enemies - perhaps a potion or magical scroll that teleports a character away. It sounds useful, but when viewed through the lens of these pillars, that ability might allow players to bypass moments of sacrifice or reduce tension by offering an easy escape - directly contradicting Tactical Tension and Heroic Sacrifice.

With the pillars in mind, I might instead design items that reinforce those experiences - perhaps something that increases both the damage a character deals and receives for a few turns, or teleports them to a random nearby tile, introducing risk and consequence.

In the end, the pillars are not rules or features; they’re distilled components of the fantasy I’m trying to create. They’re the emotional DNA of the game, guiding choices, systems, and iteration while leaving room for exploration and discovery.

.png)

Core Gameplay Systems

People approach laying the foundations for system design in different ways. Some focus on frameworks like SDT or MDA, others map out gameplay loops, or write detailed feature breakdowns. Each method has its merits - it all depends on the designer and the needs of the project.

For this document, my goal is to communicate the vision: the experience of play, not the psychology behind engagement or a theoretical breakdown of why each feature works. Applying the lenses of various design methodologies - Self-Determination Theory being one that I personally focus on - will be a continuous part of the design process, not something that serves to communicate the player-facing fantasy.

Here, the focus is on grouping the major systems and defining their place in the player’s journey - understanding what role each plays in delivering the intended fantasy. These descriptions form the foundation for designing the mechanics that will bring those systems to life.

- The Fellowship is the source of resource management and the vessel of progression.

- The Burden represents the objective - the reason for the journey - while the other characters become the means to protect it.

- Stealth adds depth to exploration by rewarding planning and observation, giving analytical players ways to gain advantages in combat.

- Enemies define the emotional weight of danger: strength is communicated through numbers, creating tension before each encounter and naturally invoking a sense of looming threat.

- Combat delivers the peak of that tension, asking players to find powerful combinations of actions and use terrain to their advantage.

- Sacrifice is a core theme, but one under the player’s control. It asks them to make difficult emotional choices, punctuating chapters of their self-authored stories.

- Progression provides mid- to long-term motivation, giving players autonomy through meaningful reward choices.

- Environmental Features pull the player forward, offering opportunities for synergy, incentivising risk, rewarding exploration, and providing short-term goals.

These definitions will guide my decisions as I move into prototyping, ensuring each system reinforces the intended player experience.

.png)

.png)

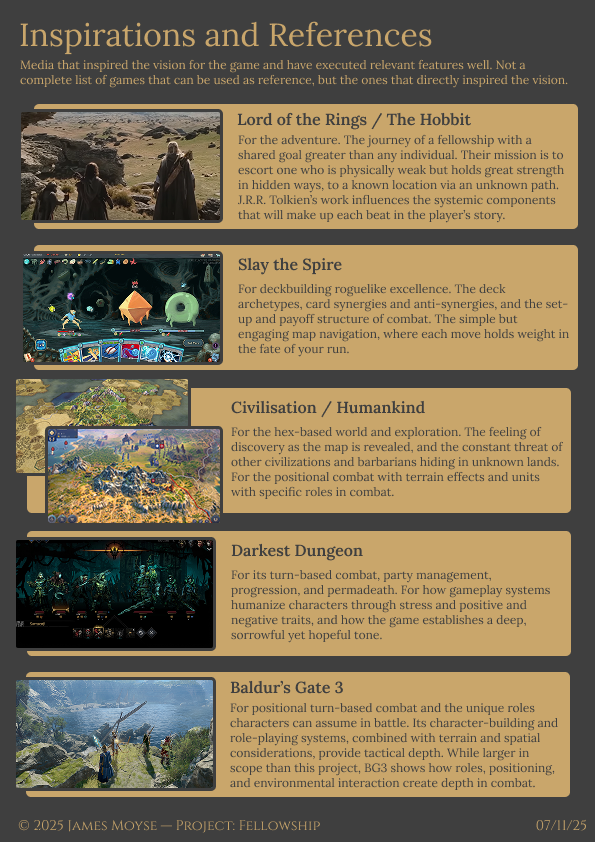

Inspirations and References

These sections aren’t intended to be an in-depth market analysis. Their purpose is, once again, aligned with the vision of this document - it’s about defining the game’s identity.

The references and inspirations listed here are works I’ve personally enjoyed and appreciated. Each has influenced this concept in some way. They execute certain ideas or features exceptionally well, and analysing them helps inform my own designs - showing how other developers solve feature-specific problems and how players expect particular interactions and interfaces to work.

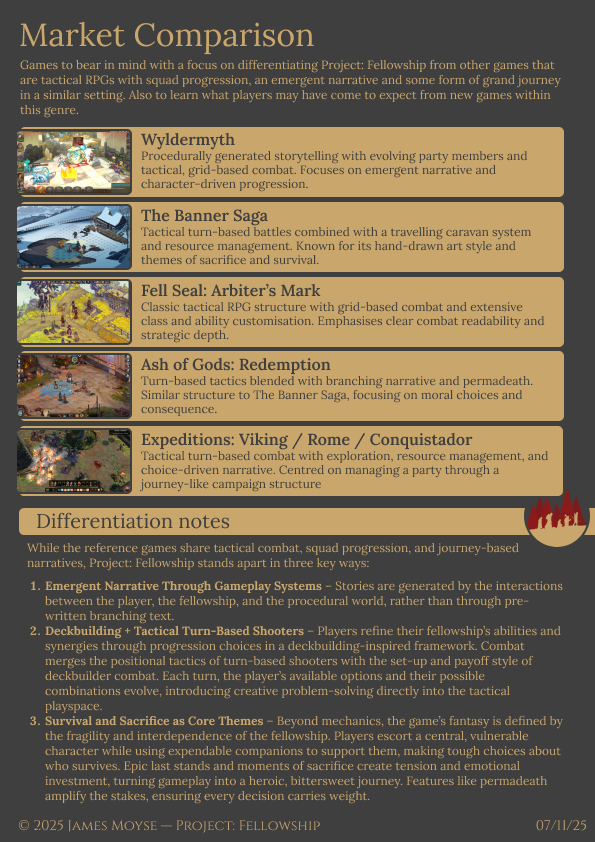

Market Comparison

This section identifies games that share similarities in setting and systems - titles with emergent narratives, tactical turn-based gameplay, party systems, and a grand journey structure within a fantasy world.

Studying these games helps ensure that this concept maintains a distinct identity - something unique to offer within its genre space. They represent not the entirety of the competition, but those most similar in experience and therefore the most important to diverge from.

They also provide valuable reference points for understanding player expectations - what players drawn to this kind of fantasy and gameplay enjoy, dislike, and anticipate from new titles.

Conclusion

This post was about defining the vision - clarifying what the game is, what it aims to make players feel, and how its systems support that experience. The next step is to begin prototyping: developing the specifics of each system, testing their interactions, and translating the concept into something tangible. From here, the focus shifts from why these systems exist to how they come to life.